Exploit Prediction Scoring System (EPSS)

I am one of the creators of EPSS, an emerging standard for predicting when software vulnerabilities will be exploited. EPSS is an open, volunteer, and entirely data-driven effort. Our goal is to assist network defenders to better prioritize vulnerability remediation efforts. While other industry standards have been useful for capturing innate characteristics of a vulnerability and provide measures of severity, they are limited in their ability to assess threat. EPSS fills that gap because it uses current threat information from CVE and real-world exploit data. The EPSS model produces a probability score between 0 and 1 (0 and 100%). Visit https://www.first.org/epss/ for more information.

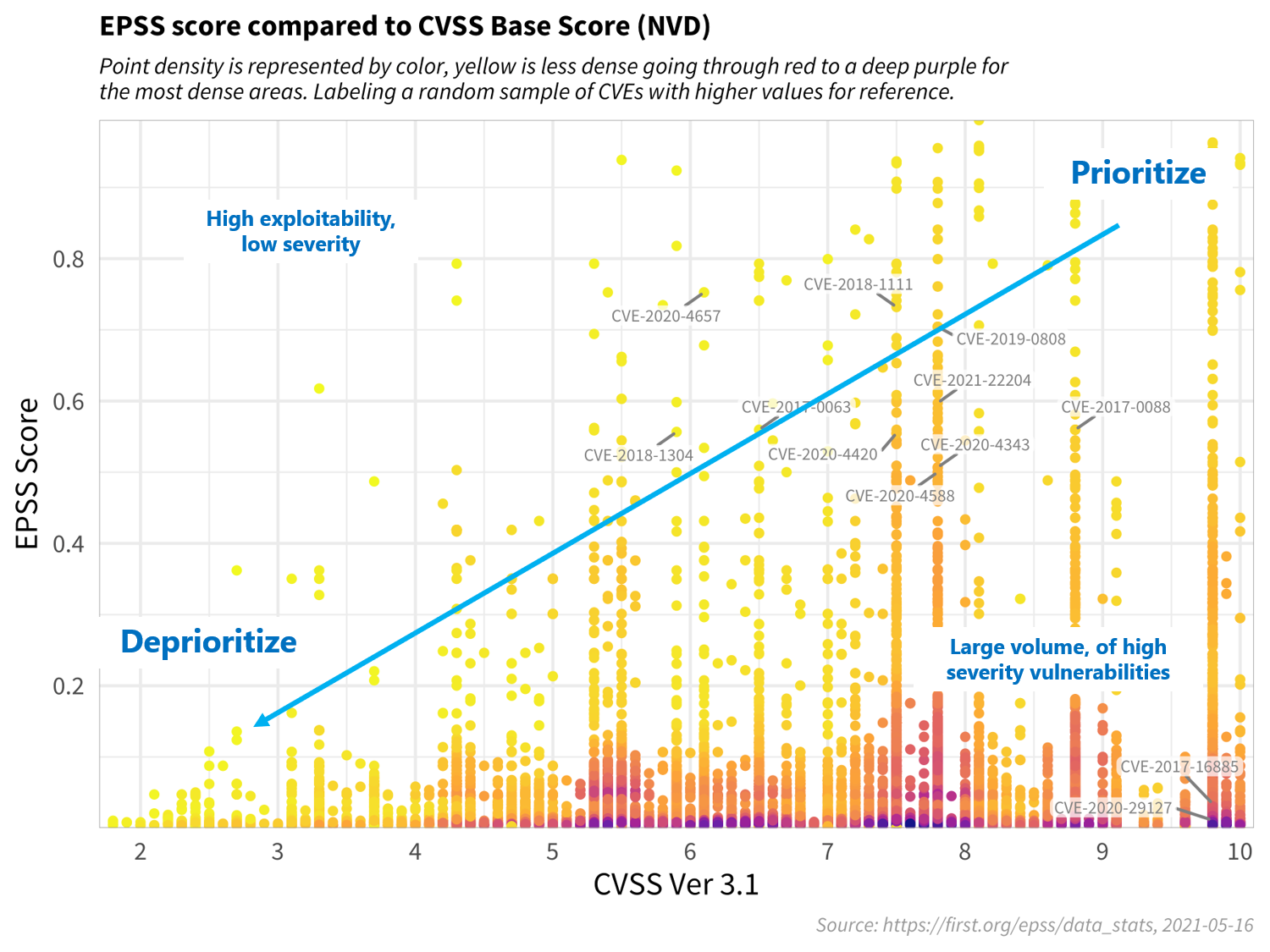

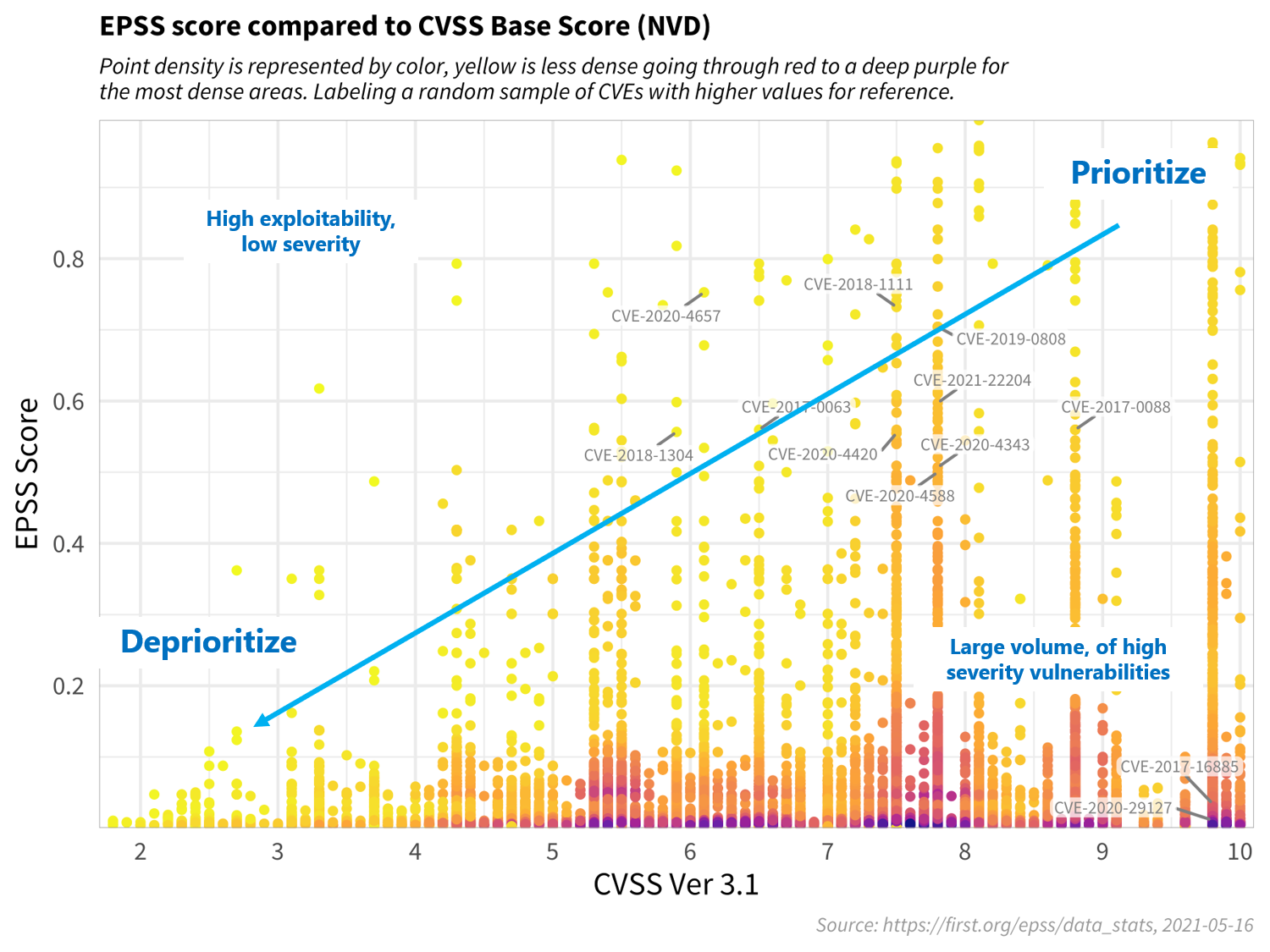

This figure plots CVSS and EPSS scores for a sample of vulnerabilities. First, observe how most vulnerabilities are concentrated near the bottom of the plot, and only a small percent of vulnerabilities have EPSS scores above 50% (0.5). While there is some correlation between EPSS and CVSS scores, overall, this plot provides suggestive evidence that attackers are not only targeting vulnerabilities that produce the greatest impact, or are necessarily easier to exploit (such as for example, an unauthenticated remote code execution). This is an important finding because it refutes a common assumption that attackers are only looking for — and using — the most severe vulnerabilities. And so, how then can a network defender choose among these vulnerabilities when deciding what to patch first? CVSS is a useful tool for capturing the fundamental properties of a vulnerability, but it needs to be used in combination with data-driven threat information, like EPSS, in order to better prioritize vulnerability remediation efforts.

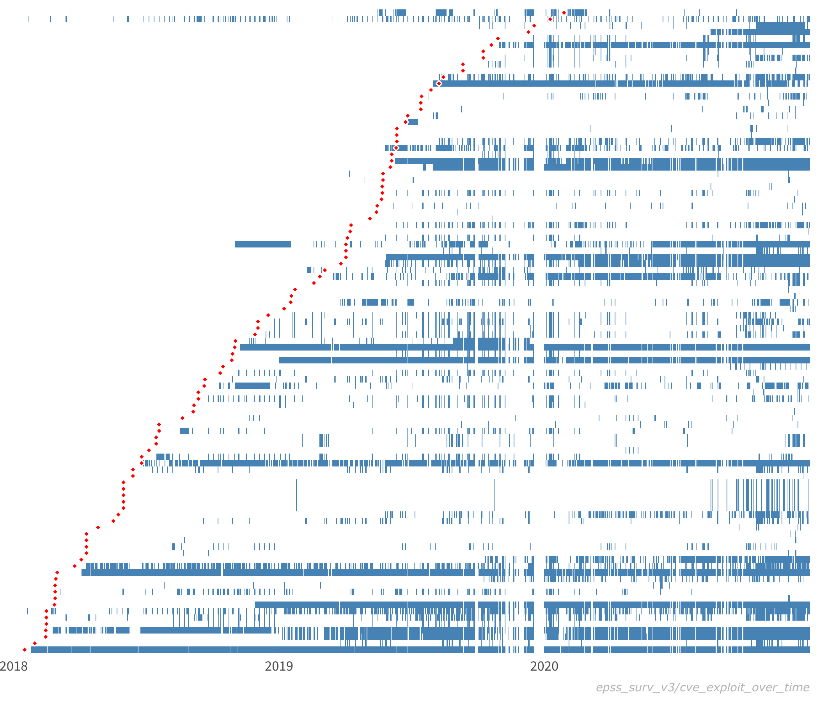

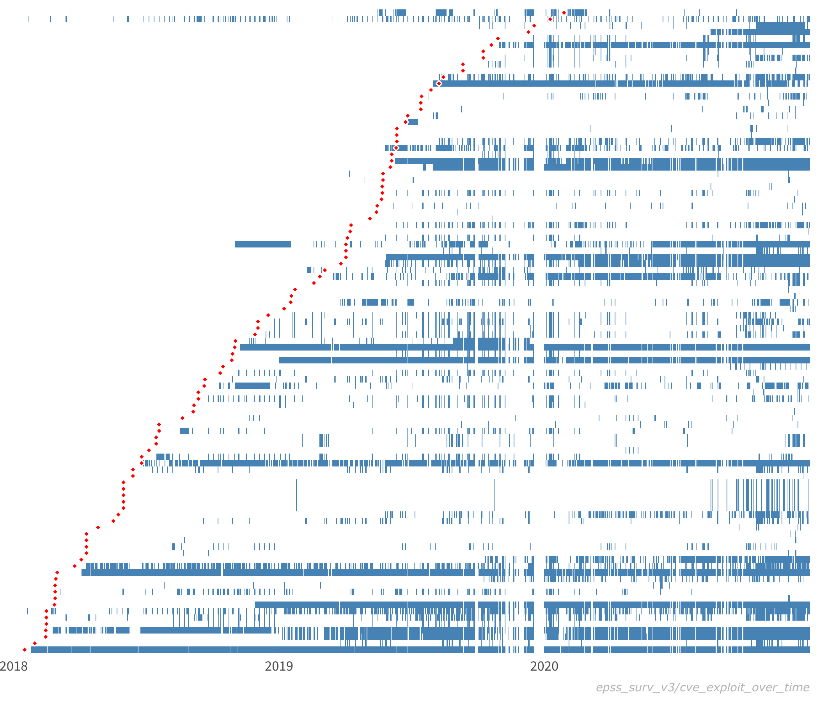

The figure shows actual exploit observations for a sample of vulnerabilities. Each row represents a separate vulnerability (CVE), while each blue line represents an observed exploit. The red dots represent the time of public disclosure of the CVE. (Note that we are not tracking whether these exploits are successful or not.) While it is difficult to draw conclusive insights from these behaviors, we can comment on general characteristics. First, simply viewing these data is interesting because they provide a novel view into real-world exploit behavior. Indeed, it is exceedingly rare to see these kinds of data publicly available, and we are fortunate to be able to share them with you. It is also thought-provoking to examine and consider the different kinds of exploit patterns, such as:

- Duration: Some vulnerabilities are exploited over a short period of time (days, weeks), while others are exploited over much longer periods of time (years). For example, some vulnerabilities in this sample have been exploited for nearly the full time window of 3 years.

- Density (intensity, prevalence): Some vulnerabilities are exploited many times during their overall duration, while others are only exploited a few times. For example, notice how exploits for some vulnerabilities occur repeatedly throughout the lifespan of the exploit, while for other vulnerabilities, there are long periods of inactivity. In addition, some vulnerabilities seem to be exploited nearly continuously (one at the bottom) and therefore appear as almost a solid blue line.

- Fragmentation: In addition to the number of times a vulnerability is exploited within its duration (i.e. density), we may also be interested in the fragmentation of exploit behavior. That is, the measure of consistent exploitation day after day, versus exploitation followed by periods of inactivity.

- Time to first exploit (delay): From the data we collect, some vulnerabilities are exploited almost immediately upon public disclosure, while for other vulnerabilities, there is a much longer delay until first observed exploit. And indeed, this figure shows a number of vulnerabilities that are exploited before public disclosure. (Given the many factors involved in CVE disclosures, we make no comment on whether or not these are proper zero day vulnerabilities.) For example, some vulnerabilities in this sample are exploited immediately, while others take 6 months or more to be exploited.

- Co-exploitation: Some vulnerabilities appear to be exploited at the same time as others. This kind of co-exploitation may be suggestive of vulnerability chaining, the practice of using multiple, successive exploits in order to compromise a target.

Common Vulnerability Scoring System (CVSS)

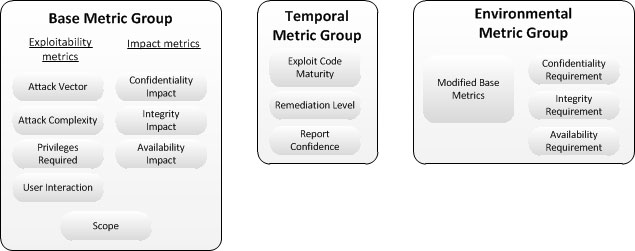

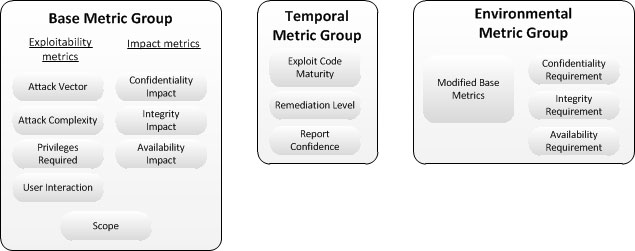

I am one of the original authors of CVSS, and have been working on it since 2003. Please see FIRST.ORG for a full description of the current standard.

Currently, corporate IT management must identify and assess vulnerabilities for many disparate hardware and software platforms. They need to prioritize these vulnerabilities and remediate those that pose the greatest risk. But when there are so many to fix, with each being scored differently across vendors, how can IT managers convert this mountain of vulnerability data into actionable information? The Common Vulnerability Scoring System (CVSS) is an open framework that addresses this issue. It offers the following benefits:

- Standardized Vulnerability Scores: When an organization normalizes vulnerability scores across all their software and hardware platforms, they can leverage a single vulnerability policy to address each of them. This policy may be similar to a service level agreement (SLA) that states how quickly a particular vulnerability must be validated and remediated.

- Prioritized Risk: When the final score is computed, the vulnerability now becomes contextual. That is, vulnerability scores are now representative of the actual risk to an organization. They know how important, in relation to other vulnerabilities, is a given vulnerability.

- Open framework: Users can be confused when a vulnerability is given a certain score. What properties gave it that score? How does it differ from this other one, or why is it not the same? With CVSS, anyone can view the exact metric values that were used to formulate the overall score.

CVSS is part of the Payment Card Industry Data Security Standard (PCI-DSS), NIST's SCAP Project, and has been formally adopted as an international standard for scoring vulnerabilities (ITU-T X.1521).

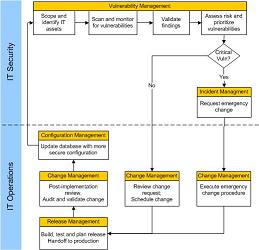

Vulnerability Management

Security Patterns

Patterns are a beautiful way of organizing and formalizing proven solutions to reoccurring problems. They were developed by Christopher Alexander in the 1970’s. Alexander observed and documented the relationships that existed between things: objects, spaces, light, people, passages, and moods. From this work emerged architectural patterns and pattern languages. This methodology was later adapted to Object Oriented (OO) programming and then Information Security. A couple of important points about patterns (especially if you ever consider writing some):

- They are very hard to write well. A “great idea” is not a pattern

- Patterns don’t represent “new” work (the way most papers do)

- They codify existing knowledge to help novices implement good solutions

- They are structured according to the 3 Part Rule

- Context: describes the general conditions under which the problem occurs

- Problem: describes the problem that repeatedly occurs and the forces that exist within the context. Forces may complement or contradict one another

- Solution: shows how to best solve the reoccurring problem, or better, how to balance the forces associated with the problem

Visit Markus Schumacher's site or hillside.net for more information on security patterns.